Special for Africa ExPress

Special for Africa ExPress

Massimo A. Alberizzi and Monica A. Mistretta

April 3, 2020

Most European airports are closed, they only open to accommodate emergency flights. Still, planes from Tehran continue to land in London, Frankfurt and Barcelona. Iran was the second outbreak of Coronavirus in the world after China, but European authorities have yet to block flights with the Middle Eastern country. In Europe, questions are raised as to when the peak will be reached: with over 33,500 deaths, Covid-19 infections are still growing.

In Iran there are more than 3,000 dead according to official estimates, but the dissidence abroad speaks of five-digit numbers.

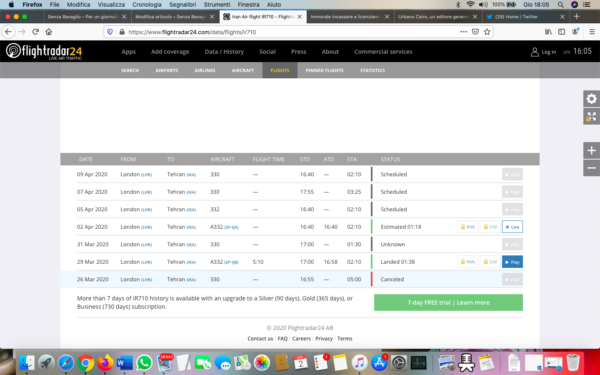

From Spain, our colleague Santiago Tarin Alonso, of the editorial staff of the newspaper La Vanguardia, tried to shed light on Barcelona’s El Prat airport, where a plane of the Iranian airline Mahan Air, linked to the Pasdaran, landed on the 26thof March. In the hours beforehand the Spanish government would have decided to stop flights. In the meantime, an Iran Air flight from Tehran landed in London the day before and the day before that it had gone back and forth between the Iranian capital and Frankfurt. In general silence, direct connections are allowed between that Middle Eastern hotbed and Europe: no one provides explanations, few ask.

On March 31, some European countries activated the Instex for the first time, the commercial mechanism created over a year ago to circumvent the US sanctions in transactions with Tehran: the United Kingdom, Germany and France sold medical material to Iran without using the international banking circuits. Washington, usually criticizing European positions on Iran, has not reacted. Indeed, the Trump administration yesterday extended the authorizations of Europe, China and Russia to Iranian nuclear activities for civil and medical purposes, as established by the 2015 agreement.

For over a year, the Instex has been subject to a heavy tug of war between Europe and the Trump administration, hostile to the mechanism created specifically to provide a commercial loophole between Tehran and European capitals. All while in Iraq, where Washington has just sent new Patriot missile batteries, the tension with Iran is sky high.

The history of the Instex had started badly: two days after the creation of the financial mechanism at the beginning of February 2019, Tehran, during the parade for the anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, had also paraded, among the flags and photos of martyrs, new cruise missiles. Europe, in embarrassment, had to react by threatening sanctions: those missiles, in fact, can carry nuclear warheads. But on the 5th of February, Tehran tested a ballistic missile with the launch of a satellite, which then failed.

The story repeats itself on February 9th of this year with the launch of the Zafar satellite. International authorities prohibit this type of experimentation in Tehran, the same which, if refined, allow the launch of nuclear warheads. The Iranian authorities instead claim that the purposes of these experiments are for civilian purposes.

But it is precisely the history of the Iranian satellites that worries and takes us once again to Europe. Investigating, you discover worrying undercurrent relationships between the European capitals and Tehran, relationships at the limit of the law in which the United States does not always play the role of spectator.

And it is precisely in Italy, in the Milanese workshops of Carlo Gavazzi Space, that the first Iranian satellite, the Mesbah, in Persian “lantern” came to be. The mother of all Tehran space launches. Iranian scientists from ITRC, the Telecommunications Research Center of Iran, and IROST, the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology, also participated in the work for the orbital microsatellite, which began in 1998. Everything seemed to go smoothly, away from prying eyes, as usual.

Costing $ 10 million, Mesbah never went into orbit. In January 2003, Iranian Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani triumphantly announces that Tehran will launch its first satellite within 18 months. “The aerospace capabilities of the Islamic Republic are one of the country’s main deterrents,” he says triumphantly. But the problems come the following year. In 2004, in fact, the president of Carlo Gavazzi Space, Manfred Fuchs – a South Tyrolean who graduated in space engineering in Germany where he founded OHB Technology in Bremen – signs a joint venture agreement with the Elbit System of Haifa, one of the flagships of the Israeli defense. For Mesbah it is the tombstone.

The satellite will remain stationary on the ground for over a decade. In 2017, Carlo Gavazzi Space will be acquired by OHB Technology. On an unspecified date, and in any case after July 2017, the now obsolete Mesbah satellite will finally reach Tehran, useful, official sources claim, for the museum of local science.

Meanwhile, Mesbah, the “lantern”, has been the beacon for all satellite developments in Tehran. The role of Europe, alongside that of Russia and China, is still unclear today. There are many obscure points and contradictions in relations between the European Union (Italy and Germany in the lead) and Iran. And a doubt arises: what happened to those 10 million dollars used to buy a satellite never launched? Returned to Iran, pocketed by someone or recycled to buy something untrustworthy by “skipping” the sanctions? Now, perhaps for the first time, the Covid-19 emergency sheds a light on inconsistencies that would otherwise have gone unnoticed: just take a look at the display boards of European airports.

Massimo A. Alberizzi

Monica A. Mistretta

massimo.alberizzi@gmail.com

monica.mistretta@gmail.com

twitter @malberizzi

twitter @monicamistrettsa