Reid Miller è andato in pensione dall’Associated Press,

come capo dell’ufficio di Seoul nel 1999.

In precedenza era stato il responsabile

dell’ufficio di Nairobi e ha seguito la guerra in Somalia

dal 1990 al 1994. E’ morto il 6 febbraio all’età di 90 anni.

Speciale per Africa ExPress

Speciale per Africa ExPress

Keith B. Richburg*

Washington, 14 febbraio 2025

(Original version in English at the end)

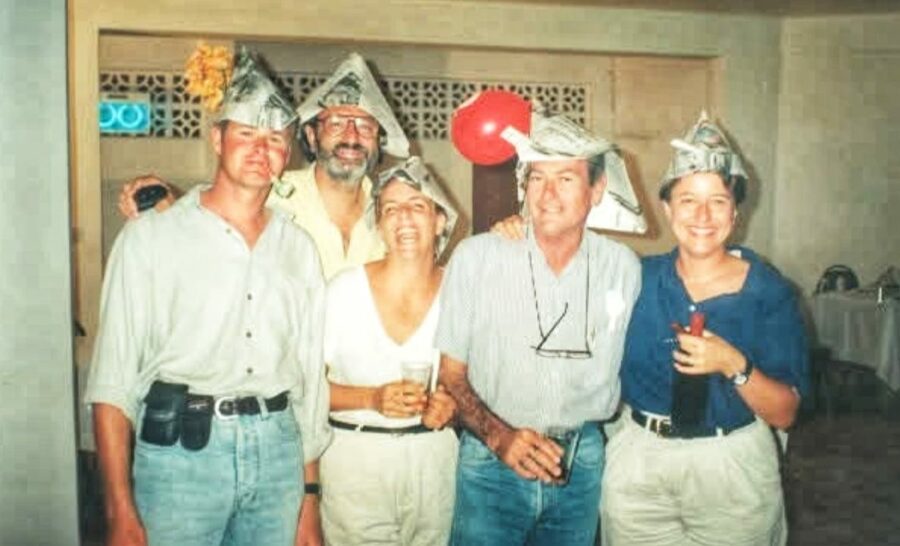

Quando sono atterrato per la prima volta a Nairobi nel 1991 e ho trovato la strada per il mio nuovo ufficio, il Washington Post Bureau, all’ultimo piano di un edificio fatiscente chiamato Chester House nel centro di Nairobi, ho incontrato un variopinto assortimento di colleghi giornalisti.

Erano spavaldi e avventurieri, vestiti con pantaloni kaki, gilet multitasche e stivali robusti, e potevano raccontarti storie infinite di sopravvivenza a incidenti aerei e di viaggi con gli eserciti ribelli mentre coprivano un continente spesso sotto copertura.

La maggior parte di loro aveva tra i 20 e i 25 anni. Io mi sentivo il vecchio del gruppo, già sulla trentina e reduce da un incarico di quattro anni nel Sud-Est asiatico e da un anno sabbatico alle Hawaii.

Poi ho incontrato Reid Miller.

Reid aveva quasi cinquant’anni ed era un esperto che aveva seguito – ed era sopravvissuto – alle guerre di guerriglia in America Centrale negli anni Ottanta. Letteralmente sopravvissuto; fu uno dei pochi che si salvò dall’esplosione di una bomba durante una conferenza stampa di un leader della guerriglia nicaraguense in un campo base che uccise tre giornalisti e molte altre persone.

Reid non ne parlava molto, a meno che non glielo si chiedesse, e di solito davanti a una bottiglia di whisky. Era discreto riguardo alle sue avventure e fughe passate.

Quando incontrai Reid nell’ufficio dell’Associated Press, in fondo al mio corridoio, la prima cosa che mi colpì fu il suo aspetto elegante. Niente giacca safari per Reid. Indossava una camicia a maniche corte stirata, pantaloni di cotone leggero con una piega così netta da poterci tagliare la carta. E mocassini marroni perfettamente lucidati.

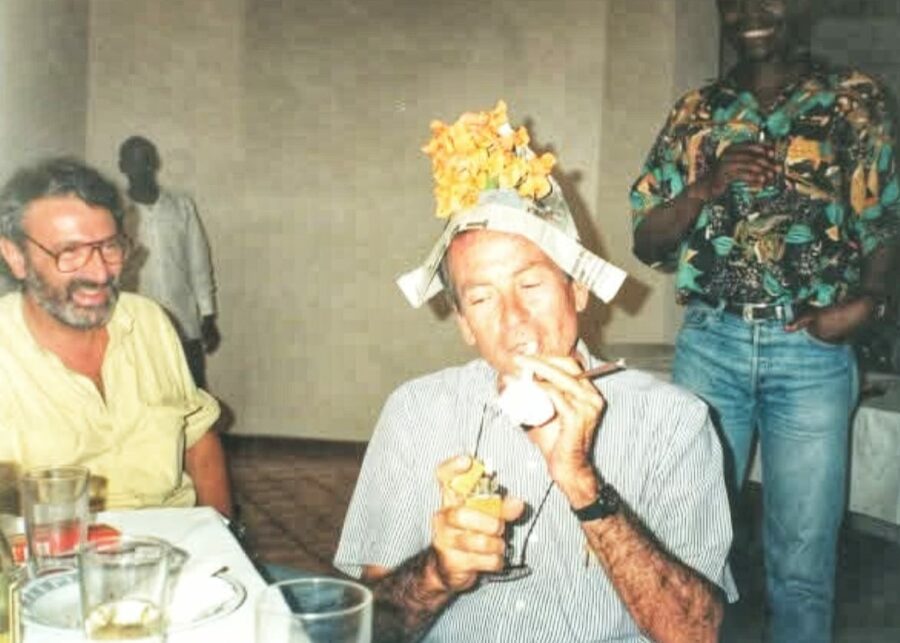

Era il capo dell’ufficio e si vestiva come tale. Ci sedemmo, lui fumò uno di quelli che sembravano una serie infinita di sigari sottili e tirò fuori da un cassetto della scrivania una bottiglia di whisky e due bicchieri.

Reid era della vecchia scuola.

Ci divertivamo a scambiarci storie di guerra: io gli raccontavo le mie imprese di copertura dei colpi di Stato e delle rivolte “popolari” in Asia, e Reid mi deliziava con le storie dell’America centrale. Lo trovavo in un certo senso uno spirito affine e mi piacevano il suo tono e i suoi modi sardonici e sobri. Reid non si vantava mai. Quando raccontava una storia divertente, di solito era lui il bersaglio della battuta.

Il mio aneddoto preferito di Reid: la capitale del Nicaragua, Managua, aveva subito un terremoto devastante che aveva distrutto gran parte del quartiere centrale degli affari, rendendo difficile la navigazione.

Una volta Reid chiese indicazioni per l’ambasciata statunitense e la gente del posto gli disse di percorrere una certa strada e di cercare un grosso cane marrone che dorme sempre all’angolo: quella è la strada da prendere per l’ambasciata. Reid disse che alcuni anni dopo, quando tornò a Managua, seppe che il grosso cane marrone era morto. Ancora una volta aveva bisogno di indicazioni per l’ambasciata. Un abitante del luogo gli disse: “Vai dritto lungo la strada dove dormiva il grande cane marrone”.

Credo di aver raccontato questa storia più di Reid.

A volte poteva essere scorbutico, burbero, qualche volta scontroso (soprattutto se interrotto per una scadenza). Ma era un buon collega e i suoi molti collaboratori più giovani lo vedevano come un mentore e un maestro. Fin dal nostro primo incontro, ricordo che il mio pensiero da trentatreenne: “Spero di poter continuare a fare questo lavoro fino all’età di Reid Miller”.

Keith B. Richburg*

*Keith B. Richburg è un giornalista americano ed ex corrispondente estero che ha lavorato per oltre 30 anni per il Washington Post. Attualmente è professore di giornalismo presso l’Università di Princeton, mentre dal 2016 al 2023 è stato direttore del Journalism and Media Studies Centre dell’Università di Hong Kong. Dal febbraio 2021 è stato presidente del Club dei corrispondenti esteri di Hong Kong fino al maggio 2023.

Keith Richburg è originario di Detroit, Michigan. Ha frequentato la Liggett School dell’Università del Michigan (BA, 1980) e la London School of Economics.

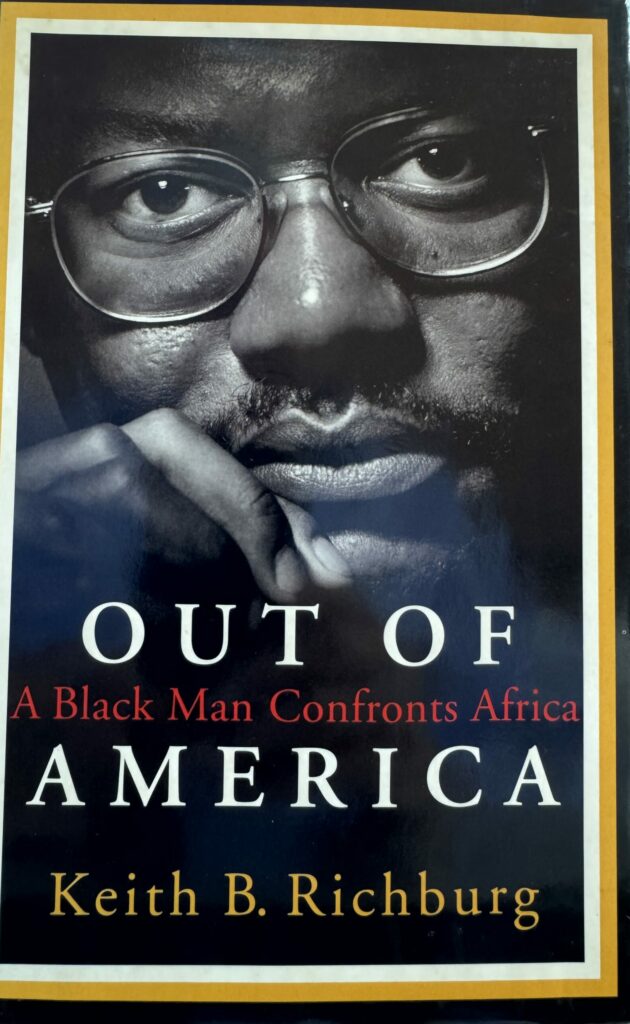

È stato corrispondente estero del Washington Post nel Sud-Est asiatico dal 1986 al 1990, in Africa a Nairobi dal 1991 al 1994, a Hong Kong dal 1995 al 2000 e a Parigi dal 2000 alla metà del 2005. È stato redattore estero del Post e capo dell’ufficio di New York del Post dal 2007 al 2010. Dal 2009 al 2012 è stato corrispondente dalla Cina per il Post con sede a Pechino e Shanghai. Ha anche coperto le guerre in Iraq e Afghanistan, attraversando a cavallo l’Hindu Kush, un viaggio che ha raccontato nella sezione Style del Post. È autore di Out of America, che racconta le sue esperienze di corrispondente in Africa, durante le quali ha assistito al genocidio del Ruanda, alla guerra civile in Somalia e a un’epidemia di colera nella Repubblica Democratica del Congo. Il libro di Richburg ha suscitato polemiche nella comunità afroamericana a causa della critica percepita nei confronti degli africani.

Reid Miller is gone: a gentleman, a friend,

an old-fashioned journalist

Africa Express Special

Africa Express Special

Keith B. Richburg**

Washington, 14 February

When I first landed in Nairobi in 1991 and found my way to my new office, the Washington Post Bureau on the top floor of a rundown building called Chester House in downtown Nairobi, I met a colorful assortment of journalism colleagues. They were swashbucklers and adventurers clad in khaki pants, multi-pocketed vests and sturdy boots, and they could regale you with endless stories of surviving plane crashes and traveling with rebel armies while covering an often undercover continent.

Most of them were in their early or mid-20s. I felt like the old man of the group, already mid-30s and just off a four year assignment covering Southeast Asia and a year-long sabbatical in Hawaii.

Then I met Reid Miller.

Reid was in his late 50s, and an experienced hand having covered — and survived — the guerrilla wars of Central America in the 1980s. Literally survived; he was one of the few who walked away from a bomb blast at a press conference by a Nicaraguan guerrilla leader at a base camp that killed three journalists and several others. Reid didn’t talk about that much, unless you asked him, and usually over a bottle of whiskey. He was understated about his own past adventures and escapes.

When I met Reid in the Associated Press Office, at the end of the hallway from mine, what struck me first was how dapper he looked. No safari bush for Reid. He was in a pressed short sleeve shirt, wearing light cotton pants with a crease so sharp you could cut paper on it. And perfectly polished brown loafers. He was the Bureau Chief, and he dressed like it. We sat down, he smoked one of what was like an endless stream of thin cigarillos and pulled a bottle of whiskey and two glasses from a desk drawer.

Reid was old school.

We enjoyed trading war stories — me, telling him my exploits covering coups and “people power” uprisings in Asia, and Reid regaling me with stories of Central America. I found him a kindred spirit in a way, and I liked his sardonic, understated tone and manner. Never any braggadocio from Reid. When he told an amusing story, he was usually the butt of the joke.

My favorite Reid yarn; Nicaragua’s capital, Managua, had suffered a devastating earthquake that destroyed much of the central business district, making it difficult to navigate. Reid was once asking directions to the U.S. Embassy, and the locals told him to do down a certain street, and look for a big brown dog that always sleeps on the corner, and that’s the road to take to the embassy. Reid said some years later when he returned to Managua, he learned the big brown dog had died. He once again needed directions to the embassy. A local told him helpfully; Go straight down the road to where the big brown dog used to sleep….

I think I’ve now told that story more than Reid.

He could sometimes be cantankerous, curmudgeonly, a few times surly (especially if interrupted on deadline). But he was good colleague, and his many younger staff members saw him as a mentor and teacher. From our first meeting, I remember my 33-year-old self thinking; I hope I can still be doing this job as long as Reid Miller.

He retired as Bureau Chief in Seoul in 1999, and passed away Feb. 6 at age 90.

Keith B. Richburg**

**Keith B. Richburg is an American journalist and former foreign correspondent who spent more than 30 years working for The Washington Post. Currently serving as the Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton University, he was the director of the Journalism and Media Studies Centre of the University of Hong Kong from 2016 to 2023. From February 2021, he has been President of the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club until May 2023.

Keith Richburg is a native of Detroit, Michigan. He attended the University Liggett School, the University of Michigan (BA, 1980) and the London School of Economics (MSc. 1985)

He served as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post in Southeast Asia from 1986 until 1990; in Africa (Nairobi) from 1991 through 1994; in Hong Kong from 1995 through 2000; and in Paris from 2000 until mid-2005. He was Foreign Editor of The Post, and was chief of the New York bureau of The Post from 2007 until 2010. He was a China correspondent for The Post based in Beijing and Shanghai from 2009 to 2012. He also covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, riding a horse partway across the Hindu Kush, a journey he chronicled in The Post’s Style section.

He is the author of Out of America, which detailed his experiences as a correspondent in Africa, during which he witnessed the Rwandan genocide, a civil war in Somalia, and a cholera epidemic in Democratic Republic of Congo. Richburg’s book provoked controversy in the African American community[3] due to its perceived criticism of Africans.

Ricordo molto bene Reid. Oltre a essere un gentiluomo e un vero amico, ricordo quando mi rimproverò perché mi vide per le strade di Mogadiscio alla guida della mia auto da solo. Quando tornai a Sahafi mi rimproverò dicendo: “Sei pazzo a guidare da solo!” mi disse con modi gentili e amichevoli mostrando viva preoccupazione.

Ho cercato di spiegare che il mio autista Ali non era arrivato e che non potevo aspettarlo. Ma lui, ovviamente e gentilmente, mi fece capire che avevo commesso un grave errore che avrebbe potuto avere conseguenze terribili. Aveva assolutamente ragione. Mi ero comportato come un idiota.

Questa sera berrò un whisky in sua memoria

Massimo Alberizzi

I remember Reid very well. Besides being a gentleman and a true friend, I remember when he scolded me because he saw me on the streets of Mogadishu driving my car alone. When I returned to Sahafi, he reprimanded me saying: ‘You are crazy to drive alone!’ he told me in a kind and friendly manner, showing deep concern.

I tried to explain that my driver Ali had not arrived and that I could not wait for him. But he obviously and kindly made me understand that I had made a serious mistake that could have had terrible consequences. He was absolutely right. I had behaved like an idiot.

Tonight I will drink a whisky in his memory.

Massimo Alberizzi

I must have done something wrong when I first arrived at Chester House in August 1991 because I quickly incurred Reid’s wrath. I can’t even remember what it was about. I was a cocksure and inexperienced reporter and I expect that I deserved it. But that is not the end of the story. In November 1994 I had the misfortune to get the wrong side of a shell fired by a tank somewhere in Southern Sudan. I suppose you could call it a very close call. The shell exploded above my head and sent shards of hot shrapnel through my backside which exited just above my left knee. I was on crutches for my next visit to Chester House and for a few weeks after that. I hated having to use crutches; I could never handle them properly. As I tried to navigate a path down the corridor in Chester House I came close to giving up. As I leant heavily against the wall, exhausted, I looked up to see Reid in front of me. His tough, leathery face was wreathed in a warm smile. His smile seemed to say: “Welcome to the club. Congratulations”. What else could I do but grin back in return? Reid was tough but kind, and truthful. A bit like Humphrey Bogart in “Casa Blanca”. And don’t we all like the character of Rick, in that film? That was Reid. The sort of man who might have tamed horses in Wyoming or taken dictators to task everywhere. Rest in Peace, Reid. I was glad to cross your path. My only regret is that I didn’t get to know better.